Loki is a hard god to pin down. Though he is known primarily to us through the Marvel Comics character he inspired as an evil, conniving, and selfish god (which he definitely is), he also plays many other roles throughout the course of Norse mythology that make him a far more complex god than all the others except perhaps Odin. At times, Loki is a trickster who plays humorous pranks on the other gods or otherwise gets them into dangerous situations. At the same time, Loki then helps the gods escape from the dangerous situations that he caused himself. Finally, Loki is often terribly malicious and undoubtedly evil. My goal in exploring Loki in many of his various roles is simply to help me understand his purpose and inclusion in the cosmology of Norse myth. Primarily because Loki, unlike the other gods, shows evidence of character development over the chronological course of the mythology and moves from being a helpful (if mischievous) friend to his fellow gods and a sworn brother of Odin, to the evil, treacherous Loki more recognizable to modern audiences. Naturally, there are issues in ascribing a modern character arc to mythology as myths can contradict other myths, which I’ll try to address, or at least point out, when and if any discrepancies actually crop up.

I’d like to first analyze Loki’s place in the cosmology. Loki is described in chapter thirty-four of Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda. He is pleasing to look upon, yet underneath the handsome facade hides his true, evil nature. More than anything, the Prose Edda points out that Loki “has the kind of wisdom known as cunning, and is treacherous in all matters.” Loki is the son of Farbauti (cruel-striker), and Laufey (who is also known as Nal). Scholarship suggests that Farbauti’s name refers to lightning, and Laufey to leaves, and says that the result of the combination of lightning and leaves is wildfire, represented by Loki. This corresponds nicely with many of the Loki myths in which he is associated with, or contests against various forms of fire. I’ll come back to this point later. His brothers are Helblindi and Byleistr though not much is known about these two. His wife is the goddess Sigyn and his two sons are Nari and Vali.

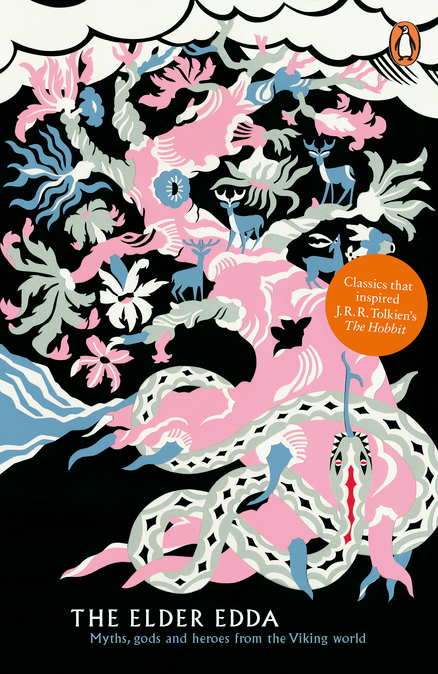

But, as the Prose Edda is quick to point out, Loki also had many monstrous children that he fathered with the giantess Angrboda. These “children” will all fight against the gods at Ragnarok. They are the giant wolf, Fenrir, the Midgard serpent, Jormungand, that is so long it can wrap itself around the world and clench its tail in its mouth, and Hel, the ruler of Niflheim and the goddess of those who die ignominious deaths. These monsters all represent various forces that will shape the world of Norse myth as it progresses. Fenrir is raised by the gods, but sensing that he will become a threat to their power, the gods who had fomerly seemingly treated him well betray him and bind him. Fenrir’s eventual escape from his bindings will be one of the various signals that Ragnarok has come. Finally, Loki is also the mother of Odin’s eight-legged horse, Sleipnir.

It’s obvious from just the above mentioned characteristics of Loki and his children that he holds a critical, yet dichotomous position in the cosmology of Norse myth. This is further emphasized by the adventures he shares with Thor and the other gods. The earliest in the chronology of Norse myth is the episode involving the Aesir and the master builder. In this episode, Loki advises the Aesir to strike a deal with a master builder that if he builds a fortress within a certain amount of time he would be given the goddes Freyja as his wife. Loki also suggests the Aesir grant the master builder use of an excellent horse named Svadilfari. When the time the Aesir allotted the master builder to complete the fortress draws near, they are distressed by the knowledge that he will finish the fortress in time and that their vow with him will be forced to stand. They blame Loki for this as he initially advised them on this matter. After the Aesir threaten to kill Loki if he doesn’t find some way out of the conundrum, Loki transforms into a mare and lures Svadilfari off into the woods. The master builder is unable to finish work on the fortress in the time the Aesir gave him without Svadilfari. Angered, the master builder reveals his true nature as a giant just as Thor returns from “hammering trolls.” The thunder god kills the master builder, and everything is resolved. Some time later, Loki gives birth to Sleipnir.

I’m just over 900 words, so I’ll call that good for this post and pick up again in the next.